Monoco Signal Briefs examine how quantitative models behave under specific assumptions. Each brief isolates a single framing, identifies its practical implications, and describes where it breaks. The objective is not certainty, but clarity.

In Brief

The framing, distilled

Volatility is easier than returns not because markets are predictable, but because volatility is more estimable under noise.

Returns ask for direction. Direction leaves a weak statistical footprint at practical horizons. Volatility asks for scale. Scale persists, clusters, and aggregates information more efficiently. The difference is not economic intuition—it is estimation geometry.

In this sense, volatility forecasting is not a prediction problem. It is an estimation problem involving a latent parameter, observed indirectly through noisy price movements. What succeeds in volatility modeling succeeds because the signal-to-noise ratio is higher for magnitude than for direction.

The implication is clarifying and uncomfortable: risk models feel reliable precisely because they focus on what can be estimated. They fail when the conditions that made estimation possible quietly disappear.

The distinction becomes clearer once we separate uncertainty about direction from uncertainty about scale.

Opening Framing

Why uncertainty has structure

Financial markets produce uncertainty in two distinct forms.

The first is directional uncertainty: whether the next move is up or down. The second is amplitude uncertainty: how large the next move might be.

Most debate in finance focuses on the first. Most risk management depends on the second.

This is not a philosophical distinction. It is a statistical one. Directional returns exhibit weak persistence and low signal-to-noise ratios. Magnitude—measured through absolute or squared returns—exhibits clustering, mean reversion, and regime structure. These properties do not make markets predictable. They make certain parameters inferable.

A useful way to think about volatility is therefore not as a market forecast, but as the expected scale of uncertainty conditional on current information. That expectation is never observed directly. It must be inferred.

Volatility is often described as “forecastable,” while returns are described as “unpredictable.” This contrast is frequently misunderstood.

Forecastability does not imply foresight. It implies structure.

Volatility forecasting succeeds because the second moment of returns evolves more slowly than the first. Large moves tend to be followed by large moves; small moves tend to be followed by small moves. This phenomenon—volatility clustering—creates persistence in magnitude even as directional outcomes remain unstable.

The error is to treat this persistence as a statement about markets being easier to read. It is not. It is a statement about what can be estimated with finite data.

When volatility forecasts are interpreted as predictions of outcomes rather than estimates of scale, risk systems inherit a false sense of control.

Volatility as an Estimation Problem

Inferring a latent scale under noise

Volatility is not observed. It is inferred.

In most practical settings, the conditional variance of returns is a latent state. Observed returns are noisy realizations drawn from a distribution whose width changes over time. The task of volatility modeling is therefore to estimate that width using incomplete information.

Once this framing is adopted, several common confusions dissolve:

The objective is not to guess the next return.

The objective is not to “predict volatility.”

The objective is to estimate a time-varying scale parameter with bounded error.

Filtering enters only as an operational consequence: when estimates are updated sequentially through time, estimation becomes filtering. But filtering is not the core insight. Estimability is.

Increasing information content changes the problem

A common proxy for volatility is the squared return. This proxy is convenient—and extremely noisy.

Single-period squared returns contain a large idiosyncratic component relative to the underlying volatility state. As a result, even strong volatility models can appear weak when evaluated against poor measurements. Low explanatory power in such regressions often reflects measurement noise, not modeling failure.

This creates a subtle institutional risk: different models with meaningfully different quality can look indistinguishable when judged against noisy targets.

Estimation theory is blunt: when signal-to-noise ratios are low, complexity does not help. Information does.

Finance offers two practical ways to increase information content.

First, aggregation across higher-frequency observations produces realized measures that converge toward the underlying integrated variance. As sampling becomes finer, measurement error shrinks.

Second, richer low-frequency summaries—such as those using high, low, open, and close prices—compress more information from the price path into a single estimate. These estimators are not cosmetic improvements; they materially reduce estimation variance.

The lesson is structural: the estimator is part of the model.

The One Equation That Matters

Measuring volatility as aggregation, not insight

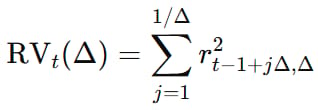

The cleanest expression of volatility estimation is realized variance:

Realized variance aggregates squared returns across finer intervals, converging to the latent integrated variance as sampling increases.

As the sampling interval Δ becomes smaller, realized variance converges to the latent integrated variance. This is not a modeling assumption. This convergence result is one of the rare cases in finance where increasing data density provably improves the identifiability of a latent state. It is a measurement result.

The equation matters because it encodes three ideas at once:

Volatility estimation improves through aggregation

Magnitude accumulates information faster than direction

Better measurement reduces the illusion of poor forecasting

GARCH-type models may stabilize estimates, but they are secondary to this principle. Measurement comes first.

A Parallel to Momentum

Signed versus unsigned estimability

Momentum and volatility are often discussed together, but they operate on different objects.

Momentum attempts to extract structure from signed returns. Volatility extracts structure from unsigned returns.

Both are attempts to detect persistence. But magnitude is easier to estimate than direction because it survives aggregation. Direction cancels.

This distinction matters because it clarifies a recurring confusion: detecting structure is not the same as monetizing it. Volatility can be estimable without being exploitable. Momentum can be detectable without being durable.

Estimability is a necessary condition for monetization, not a sufficient one.

Failure Mode

When estimation assumptions quietly break

Volatility models rarely fail suddenly. They fail quietly.

They fail first when measurement assumptions degrade: sparse sampling, market closures, microstructure noise, or jump-dominated dynamics. The estimator continues to produce numbers, but those numbers no longer correspond to the underlying state.

They fail next when regimes shift. Volatility becomes discontinuous, correlations change abruptly, and the latent process no longer resembles the one being estimated.

The danger is not that volatility stops being estimable. The danger is that institutions do not notice when it stops being estimable.

Implication

Why risk models fail quietly before they fail loudly

Modern risk systems are built on volatility because volatility is the most estimable object in markets. Risk parity, volatility targeting, and capital allocation all depend on it.

This reliance creates a structural vulnerability.

Low-volatility regimes encourage scale. Scale amplifies exposure. When regimes change, volatility does not merely rise—it changes character. Estimation error widens precisely when confidence is highest.

There is no paradox here. There is a design constraint.

Risk systems are not fragile because they rely on volatility. They are fragile because they rarely test whether volatility remains estimable.

Conceptual Lineage

Ideas that inform the framing

Detection & Estimation Foundations

Van Trees, Detection, Estimation, and Modulation Theory

Volatility as a Latent Process

Andersen, Bollerslev, Diebold — realized volatility and integrated variance

Poon — volatility forecasting surveys

Measurement and Estimator Efficiency

Garman & Klass — OHLC volatility estimation

Meilijson — estimator efficiency and bounds

Institutional Practice & Regime Risk

Lazard Asset Management — Predicting Volatility

Avellaneda — Trading Market Volatility

CME Group — volatility estimation notes

Disclaimer

This material is provided for educational and informational purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice, a recommendation, or an offer to buy or sell any security or financial instrument. The views expressed are based on stated assumptions and simplified models and may not reflect real-world market conditions. Monoco does not manage assets or provide personalized financial advice.

© 2025 Monoco Research